Zeitschrift

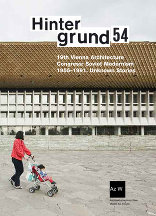

Hintergrund 54

19th Vienna Architecture Congress: Soviet Modernism 1955-1991

The Republic of Red Scarves The Artek Pioneer Camp in the Crimea

13. Mai 2013 - Wolfgang Kil

Artek, the most renowned children’s vacation camp in the Soviet Union, is located on the coast of the Black Sea, on the Crimean peninsula. Five complexes that are named after their topographical site are distributed over a length of seven and a half kilometres and a surface measuring almost three hundred hectares: Morskoy (Sea Camp), Pribrezhny (Coast Camp), Gorny (Mountain Camp), Kiparisny (Cypress Camp) and Lazurny (Ocean Blue Camp). In several expansion phases additional room was created to accommodate up to 32 000 boys and girls a year, who were looked after by almost 2000 adults. In the summer vacation months up to 5000 children could stay there.

In particular Morskoy, the „Sea Camp“, with its striking cubes constructed of concrete and glass is today seen as the symbol of Artek. Against the backdrop of the enormous slope of Aju Dag (Bear Mountain), the cubes floating lightly over the beach were „the dream of all Soviet and post-Soviet children of freedom, the distant sign of a city of happiness on the Crimean peninsula.“[1] Children could distinguish the four identical pavilions by their colours – from red to blue, and orange to marine green. On top of the flat roofs, which afforded a view of the sea, children could play under a light sunroof. There were four sleeping rooms in each pavilion, two for boys and two for girls. „In each room there were beds for ten to twelve children. This corresponded to the smallest social unit: a pioneer brigade. The next largest social unit is the pioneer group consisting in three or four brigades. Each cube of the Morskoy camp thus accommodates a pioneer group.“[2] At the end of the row there was a fifth pavilion, which, in contrast to the others, was intended to be used by adult leaders and guests who stayed in rooms with two beds and a private balcony.

By the end of the 1960s, a total of 36 buildings had been erected in Artek, including living and sleeping space, eight dining halls (originally covered outdoor canteens), a school with room for a 1000 students, a medical centre, a stadium for 10 000 spectators, two sea-water swimming pools, a museum, a film studio, and a port with a sailing club. Later further buildings were added – for instance a gymnasium in 1981, or the swimming pool of the Mountain Camp – elements that embody the completely different formal repertory of the Brezhnev years and thus disrupt the otherwise wonderfully harmonious ensemble.

The history of the vacation camp reaches far back into the early period of the Soviet Union. Zinovy Solovyov, chairman of the Russian Red Cross at the time, a close friend of Lenin and himself plagued with tuberculosis, wanted to also give children from socially marginalised and unhealthy living conditions access to the salutary climate of the Black Sea. At his order the camp’s operation began in the summer of 1925 with a few tents.

A longer phase with wooden barracks and the first ceremonial communal buildings was to be followed by a master plan for a large Artek elaborated by Ivan Leonidov from 1935 on, and published in Arkhitektura SSSR in 1938. War and the German occupation of Crimea in 1941–1944 prevented the plans from being implemented. After Hitler’s Wehrmacht was expelled, nothing remained of the children’s camp, but its immediate reconstruction meant that it was founded again. Even if Stalin had announced ambitious plans, the concrete buildings only proceeded haltingly. A few buildings such as the Pioneer’s Palace or a pretentious dining hall from 1953/54 today serve as testimony to the period of „Socialist Realism“ and its characteristic neo-classicist architecture.

„In reality“, as we can glean from Bohdan Tscherke’s remarks, „there is – apart from doctors, educators and architects – one person without whom the New Artek never would have been built: Nikita Khrushchev.“ This was the party chief who noted the following in his memoirs: „People would like to have their freedom, to live better and to satisfy their needs. They say: Why do you promise us a better life in the next world? Give us some happiness on earth.“[3]

In 1957, an architectural competition was advertised for the expansion of Artek – and the winner was a young architects’ collective from Moscow. The prize-winners had developed a construction kit out of pre-fabricated reinforced concrete elements with which very different buildings could be built with effectively and with great precision. In this way they made their debut by clearly committing themselves to industrial construction. The head of the collective, Anatoly Polyansky, was only 29 at the time of the competition and thus, as Arne Winkelmann writes in his dissertation from 2003, „had not yet appeared with any larger construction. It was not until 1958 that with his participation in the design of the Soviet pavilion at the World Exposition in Brussels he was to join the ranks of more well-known architects.“[4]

Yet let us return to the years after Stalin’s death. A turning point, everything was in flux! Young, unexhausted forces were sought, and so it was possible that someone completely unknown could become the man of the hour. Especially if he promised not only to assemble houses like tractors, but to let them glide, even fly like in an animated dream! In 1961 the first buildings from Polyansky’s building kit were ready to move into. As a contemporary enthusiastically reported: „Using pre-fab concrete pieces made it possible to raise seven pavilions within eight month’s time. Thanks to the frame constructions, it was not necessary to do large-scale excavation work in spite of the complicated land profile on the bluff.“[5] Indeed, even the historian can only sing his praises in retrospect:

“Even though they were all constructed out of the same prefab pieces, given their variations in length, width and height, the way they have been embedded in the landscape with great care and their colourful design, they all look pleasantly different. […] Khrushchev’s dream of industrial construction had found its most beautiful manifestation here!”[6]

In 2003, one year after the exhibition Glück Stadt Raum in Europa 1945–2000 at the Berlin Akademie der Künste, I had a chance to make a brief excursion to Artek while visiting the Crimean peninsula. I wanted to see what remained of the camp and its famous architecture following the end of the Soviet Union, and the transformation of the former pioneer camp into an „International Centre for Children“ under the auspices of the Ukrainian government. The government, with different degrees of success, prevented the commercial privatisation of the complex and – to this day – has managed to maintain the operation of the international camp.

Without knowing it, I was one of the last visitors to see Polyansky’s camp buildings in their original form as shortly afterwards a large reconstruction took place, which turned the pioneer paradise into a holiday resort for the youngsters of parents who were financially better off. „Today the children no longer wear scarves at Artek,“ as we can read in the journal Mare. „More than 60 percent of the camp guests (in the summer up to almost 90 percent) come to Artek because they can afford it. 600 dollars for three weeks room and board in a twelve-bed room – in countries where the minimum wage is 60 dollars a month this is a lot of money. Most children are between nine and 16 years of age. Many are here at their parents’ wish.“[7]

The „Republic of Red Scarves“ is now history. The brutal reconstruction has destroyed Anatoly Polyansky’s New Artek, which nevertheless continues to exert a fascination to this very day. A moment of remorse should be allowed among friends of good architecture! The question of assessing this historical milestone of architecture has thus assumed a new urgency. „Any architecturally trained eye will wallow in reminiscences, so clear the expression of modernity in concrete, steel and glass,“[8] as a group of students from Weimar enthused in 2000 even though they knew that: “One had to earn the right to spend a summer on the Black Sea with the best grades in school, good behaviour and social as well as political involvement. […] The program was largely directed to the formation of a Soviet elite. Everything there served this one sole goal...”[9]

And thus we are once again confronted with the gnawing question, which has made any exploration of the 20th century painful: How is it possible to live the right life in the wrong time? This rift can be traced throughout the entire century, and can be illustrated with the following three historical cases.

Germany – The KdF-Spa Prora on the island of Rügen Sanatoriums for the regeneration of the masses were a phenomenon that was pursued worldwide with great interest. This is why Clemens Klotz received a gold medal for the megalomaniac, but also serially structured and well thought-out design that he submitted to the world exposition in Paris 1937. “A sea spa for 20 000 vacationers, thousands of rooms with a view of the sea… at the time this was certainly progressive and was bound to impress both architects, social politicians and vacation organisers.”[10] But Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper called Prora an example of Nazi-Architecture, indeed: „While Clemens Klotz copies the forms of a building by Mendelsohn, Erich Mendelsohn as a Jew remained safe only in exile. The adopted form can, however, continue to be good.“[11] Or at least useful – as the spa illustrates today having been expanded to serve as a youth hostel.

Italy – The Colonie di Infanzia In a review of a book of photographs about the children’s camps of Italian Fascismo, we read: “What makes these buildings so significant? It is certainly the tangible, obvious contradiction between on the one hand, the architectural forms that in most colonies are in the style of rationalism, that is the Italian variant of modernism, and on the other the content, which is the paramilitary training of children in a totalitarian system. This contradiction is particularly strongly noted outside of Italy. […] Following the end of the Fascist SPUK the children’s camps were still used, until from the 1960s on – as it was elsewhere – the trend became to prefer individual family vacations.”[12] As one sees, the reviewer was neither able to praise nor to dismiss the buildings depicted.

Israel – The Kibbuzim While the third reference might seem a bit out of place here, I wanted to show those images with which the curators of the Israeli pavilion at the Architecture Biennale in Venice 2010 surprised not only me. Here historical photographs of Kibbutz buildings – all magnificent examples of a radiant white modernist style built in the desert sand – were contrasted with scenes from the at times strictly collectivist settlement life. The declared intention was to commemorate the socialist legacy of the settlers’ movement, which even in Israel has fallen into oblivion. That this legacy had its ugly side was not hidden, as was shown by the photo depicting Kibbuzniks mourning in front of the veiled portrait of Stalin after his death.

If one compares Artek with Prora, or the Italian childrens’ camps from the perspective of their complex relationship to modernity, then doesn’t the Crimean project clearly come out better? Do we really want to hold it against that project that we now have other models of recreation for young people today? The assessment that Arne Winkelmann ultimately arrives at in his dissertation is ambivalent. While he certainly does acknowledge that „in no other states were such large amounts spent on the education, training and entertainment of children as in the Soviet Union of the sixties.“ Yet without putting it all into perspective one can not draw an accurate picture: “It was with great effort and expense that the government staged these places of „happy childhood“ and seeming self-determination, and by doing so kept control over the activities of children and young people.”

With this “yes, but…” one remains within the bounds of today’s research into socialism. Here a picture is usually drawn of a society that is becoming increasingly foreign to us, a picture that is limited to the power structures and repression of socialism. Power is assumed as an end in itself and too seldom is it asked whether the formation and use of power were not also based on a social concept or even a vision. What purpose did this entire effort, this expenditure serve? For what purpose did this omnipresent state penetrate all spheres, regulating and dominating everything?

Ten years after the fall of the Iron Curtain the large exhibition Glück. Stadt. Raum („Happiness. City. Space“) tried to compare systems in a cultural historical sense. To the amazement of many, it discovered a surprising number of affinities between private and collective ideals and desires behind the fronts of the Cold War. While we, under the sway of liberalism, had already gotten used to tracking down anything that reeked of totalitarianism within the modernity of the social welfare state, the question suddenly snuck in the backdoor: To what extent were the classical values and hopes of social democracy actually at work in state socialism?

Spurred on by this question and remembering the Khrushchev-quote „Give us some happiness on earth!“, I would agree with Winkelmann’s final verdict that refers to Artek’s symbolic political importance:

“Artek is more an architectural creed than just an architectural document of the political „Thaw“. No other building and no other architectural complex in the Soviet Union illustrates the euphoria and the hope of people in this time, among so many other aspects. […] The transparency and openness of architecture and the generous scale of the facility are in a sense metaphoric of a sigh of relief following the Stalinist terror. […] Artek was supposed to be a beacon showing the world the new age in the Soviet Union.”[13]

Small addendum

Certainly not everything that today strikes us as acceptable or even worth commemorating in the legacy of state socialism was wrested from those in power or was created in niches at a remove from the party. Even the „leading cadres“ of the party state were not the homogenous caste they are usually portrayed as today. These were people with rather different characters, with their own experiences and ideas, among which one was able, when necessary, to find allies.

In the publications on Artek I discovered a sheet with a sketch by Polyansky that I found touching and made me think of my own early years at the drawing board. There they were again, the dream-like, blissful hours of the unhindered explorer who, full of exuberance, illuminates the ground plan and the section of his waterside pavilion with one sun. To overcome gravity in such a way, to leave behind Euclidean space – this is not something that an accomplice of power is capable of pulling off, and I’ve also rarely seen a dissident who was so laid-back. I simply believe that we – to paraphrase Camus – have to imagine the architect of the New Artek as a happy individual. That his sketches would then actually bring forth buildings, this is something others have decided.

[01] Bohdan Tscherkes, „Zauber meiner Seele. Anatoli Poljanski und die Pionierrepublik Artek auf der Krim“, Glück Stadt Raum in Europa 1945–2000. Romana Schneider and Rudolf Stegers (eds). Basel: Birkhäuser, 2002, p. 76 ff.

[02] Ibid.

[03] Ibid.

[04] Arne Winkelmamnn, Das Pionierlager Artek. Realität und Utopie in der sowjetischen Architektur der sechziger Jahre. Dissertation at the Bauhaus University Weimar, 2003. PDF-Download: http://knigi.suuk.su/architektur_de-1.pdf

[05] Liv Falkenberg, „Neubauten in Artek“, Deutsche Architektur, Vol. 1 (1962), p. 46. In the German Democratic Republic Polyansky’s buildings were immediately presented by a number of illustrations in the professional journal Deutsche Architektur. This was immediately followed by a discussion of Pier Luigi Nervi’s „Palace of Labor“ that had just been completed in Turin.

[06] Bohdan Tscherkes, op. cit.

[07] Stefanie Flamm, „Im Paradies der Pioniere“, Mare, No. 34, October 2002.

[08] Martin Fröhlich, „Der Rundgang“, Bauwelt, vol. 16 (2000), p. 23.

[09] Bohdan Tscherkes, op. cit.

[10] Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper, „Das KdF-Bad Prora auf Rügen. Ein Versuch über Architektur und Moral“, Das Kunstwerk als Geschichtsdokument. Annette Tietenberg (ed.). Munich: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1999, p. 153.

[11] Ibid, p. 154.

[12] Benedikt Hotze, „Der verlassene Faschismus“, Baunetzwoche, No. 291, Oct. 12, 2012. Download: www.baunetz.de/cid/2981133

[13] Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper, op. cit., p. 157.

In particular Morskoy, the „Sea Camp“, with its striking cubes constructed of concrete and glass is today seen as the symbol of Artek. Against the backdrop of the enormous slope of Aju Dag (Bear Mountain), the cubes floating lightly over the beach were „the dream of all Soviet and post-Soviet children of freedom, the distant sign of a city of happiness on the Crimean peninsula.“[1] Children could distinguish the four identical pavilions by their colours – from red to blue, and orange to marine green. On top of the flat roofs, which afforded a view of the sea, children could play under a light sunroof. There were four sleeping rooms in each pavilion, two for boys and two for girls. „In each room there were beds for ten to twelve children. This corresponded to the smallest social unit: a pioneer brigade. The next largest social unit is the pioneer group consisting in three or four brigades. Each cube of the Morskoy camp thus accommodates a pioneer group.“[2] At the end of the row there was a fifth pavilion, which, in contrast to the others, was intended to be used by adult leaders and guests who stayed in rooms with two beds and a private balcony.

By the end of the 1960s, a total of 36 buildings had been erected in Artek, including living and sleeping space, eight dining halls (originally covered outdoor canteens), a school with room for a 1000 students, a medical centre, a stadium for 10 000 spectators, two sea-water swimming pools, a museum, a film studio, and a port with a sailing club. Later further buildings were added – for instance a gymnasium in 1981, or the swimming pool of the Mountain Camp – elements that embody the completely different formal repertory of the Brezhnev years and thus disrupt the otherwise wonderfully harmonious ensemble.

The history of the vacation camp reaches far back into the early period of the Soviet Union. Zinovy Solovyov, chairman of the Russian Red Cross at the time, a close friend of Lenin and himself plagued with tuberculosis, wanted to also give children from socially marginalised and unhealthy living conditions access to the salutary climate of the Black Sea. At his order the camp’s operation began in the summer of 1925 with a few tents.

A longer phase with wooden barracks and the first ceremonial communal buildings was to be followed by a master plan for a large Artek elaborated by Ivan Leonidov from 1935 on, and published in Arkhitektura SSSR in 1938. War and the German occupation of Crimea in 1941–1944 prevented the plans from being implemented. After Hitler’s Wehrmacht was expelled, nothing remained of the children’s camp, but its immediate reconstruction meant that it was founded again. Even if Stalin had announced ambitious plans, the concrete buildings only proceeded haltingly. A few buildings such as the Pioneer’s Palace or a pretentious dining hall from 1953/54 today serve as testimony to the period of „Socialist Realism“ and its characteristic neo-classicist architecture.

„In reality“, as we can glean from Bohdan Tscherke’s remarks, „there is – apart from doctors, educators and architects – one person without whom the New Artek never would have been built: Nikita Khrushchev.“ This was the party chief who noted the following in his memoirs: „People would like to have their freedom, to live better and to satisfy their needs. They say: Why do you promise us a better life in the next world? Give us some happiness on earth.“[3]

In 1957, an architectural competition was advertised for the expansion of Artek – and the winner was a young architects’ collective from Moscow. The prize-winners had developed a construction kit out of pre-fabricated reinforced concrete elements with which very different buildings could be built with effectively and with great precision. In this way they made their debut by clearly committing themselves to industrial construction. The head of the collective, Anatoly Polyansky, was only 29 at the time of the competition and thus, as Arne Winkelmann writes in his dissertation from 2003, „had not yet appeared with any larger construction. It was not until 1958 that with his participation in the design of the Soviet pavilion at the World Exposition in Brussels he was to join the ranks of more well-known architects.“[4]

Yet let us return to the years after Stalin’s death. A turning point, everything was in flux! Young, unexhausted forces were sought, and so it was possible that someone completely unknown could become the man of the hour. Especially if he promised not only to assemble houses like tractors, but to let them glide, even fly like in an animated dream! In 1961 the first buildings from Polyansky’s building kit were ready to move into. As a contemporary enthusiastically reported: „Using pre-fab concrete pieces made it possible to raise seven pavilions within eight month’s time. Thanks to the frame constructions, it was not necessary to do large-scale excavation work in spite of the complicated land profile on the bluff.“[5] Indeed, even the historian can only sing his praises in retrospect:

“Even though they were all constructed out of the same prefab pieces, given their variations in length, width and height, the way they have been embedded in the landscape with great care and their colourful design, they all look pleasantly different. […] Khrushchev’s dream of industrial construction had found its most beautiful manifestation here!”[6]

In 2003, one year after the exhibition Glück Stadt Raum in Europa 1945–2000 at the Berlin Akademie der Künste, I had a chance to make a brief excursion to Artek while visiting the Crimean peninsula. I wanted to see what remained of the camp and its famous architecture following the end of the Soviet Union, and the transformation of the former pioneer camp into an „International Centre for Children“ under the auspices of the Ukrainian government. The government, with different degrees of success, prevented the commercial privatisation of the complex and – to this day – has managed to maintain the operation of the international camp.

Without knowing it, I was one of the last visitors to see Polyansky’s camp buildings in their original form as shortly afterwards a large reconstruction took place, which turned the pioneer paradise into a holiday resort for the youngsters of parents who were financially better off. „Today the children no longer wear scarves at Artek,“ as we can read in the journal Mare. „More than 60 percent of the camp guests (in the summer up to almost 90 percent) come to Artek because they can afford it. 600 dollars for three weeks room and board in a twelve-bed room – in countries where the minimum wage is 60 dollars a month this is a lot of money. Most children are between nine and 16 years of age. Many are here at their parents’ wish.“[7]

The „Republic of Red Scarves“ is now history. The brutal reconstruction has destroyed Anatoly Polyansky’s New Artek, which nevertheless continues to exert a fascination to this very day. A moment of remorse should be allowed among friends of good architecture! The question of assessing this historical milestone of architecture has thus assumed a new urgency. „Any architecturally trained eye will wallow in reminiscences, so clear the expression of modernity in concrete, steel and glass,“[8] as a group of students from Weimar enthused in 2000 even though they knew that: “One had to earn the right to spend a summer on the Black Sea with the best grades in school, good behaviour and social as well as political involvement. […] The program was largely directed to the formation of a Soviet elite. Everything there served this one sole goal...”[9]

And thus we are once again confronted with the gnawing question, which has made any exploration of the 20th century painful: How is it possible to live the right life in the wrong time? This rift can be traced throughout the entire century, and can be illustrated with the following three historical cases.

Germany – The KdF-Spa Prora on the island of Rügen Sanatoriums for the regeneration of the masses were a phenomenon that was pursued worldwide with great interest. This is why Clemens Klotz received a gold medal for the megalomaniac, but also serially structured and well thought-out design that he submitted to the world exposition in Paris 1937. “A sea spa for 20 000 vacationers, thousands of rooms with a view of the sea… at the time this was certainly progressive and was bound to impress both architects, social politicians and vacation organisers.”[10] But Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper called Prora an example of Nazi-Architecture, indeed: „While Clemens Klotz copies the forms of a building by Mendelsohn, Erich Mendelsohn as a Jew remained safe only in exile. The adopted form can, however, continue to be good.“[11] Or at least useful – as the spa illustrates today having been expanded to serve as a youth hostel.

Italy – The Colonie di Infanzia In a review of a book of photographs about the children’s camps of Italian Fascismo, we read: “What makes these buildings so significant? It is certainly the tangible, obvious contradiction between on the one hand, the architectural forms that in most colonies are in the style of rationalism, that is the Italian variant of modernism, and on the other the content, which is the paramilitary training of children in a totalitarian system. This contradiction is particularly strongly noted outside of Italy. […] Following the end of the Fascist SPUK the children’s camps were still used, until from the 1960s on – as it was elsewhere – the trend became to prefer individual family vacations.”[12] As one sees, the reviewer was neither able to praise nor to dismiss the buildings depicted.

Israel – The Kibbuzim While the third reference might seem a bit out of place here, I wanted to show those images with which the curators of the Israeli pavilion at the Architecture Biennale in Venice 2010 surprised not only me. Here historical photographs of Kibbutz buildings – all magnificent examples of a radiant white modernist style built in the desert sand – were contrasted with scenes from the at times strictly collectivist settlement life. The declared intention was to commemorate the socialist legacy of the settlers’ movement, which even in Israel has fallen into oblivion. That this legacy had its ugly side was not hidden, as was shown by the photo depicting Kibbuzniks mourning in front of the veiled portrait of Stalin after his death.

If one compares Artek with Prora, or the Italian childrens’ camps from the perspective of their complex relationship to modernity, then doesn’t the Crimean project clearly come out better? Do we really want to hold it against that project that we now have other models of recreation for young people today? The assessment that Arne Winkelmann ultimately arrives at in his dissertation is ambivalent. While he certainly does acknowledge that „in no other states were such large amounts spent on the education, training and entertainment of children as in the Soviet Union of the sixties.“ Yet without putting it all into perspective one can not draw an accurate picture: “It was with great effort and expense that the government staged these places of „happy childhood“ and seeming self-determination, and by doing so kept control over the activities of children and young people.”

With this “yes, but…” one remains within the bounds of today’s research into socialism. Here a picture is usually drawn of a society that is becoming increasingly foreign to us, a picture that is limited to the power structures and repression of socialism. Power is assumed as an end in itself and too seldom is it asked whether the formation and use of power were not also based on a social concept or even a vision. What purpose did this entire effort, this expenditure serve? For what purpose did this omnipresent state penetrate all spheres, regulating and dominating everything?

Ten years after the fall of the Iron Curtain the large exhibition Glück. Stadt. Raum („Happiness. City. Space“) tried to compare systems in a cultural historical sense. To the amazement of many, it discovered a surprising number of affinities between private and collective ideals and desires behind the fronts of the Cold War. While we, under the sway of liberalism, had already gotten used to tracking down anything that reeked of totalitarianism within the modernity of the social welfare state, the question suddenly snuck in the backdoor: To what extent were the classical values and hopes of social democracy actually at work in state socialism?

Spurred on by this question and remembering the Khrushchev-quote „Give us some happiness on earth!“, I would agree with Winkelmann’s final verdict that refers to Artek’s symbolic political importance:

“Artek is more an architectural creed than just an architectural document of the political „Thaw“. No other building and no other architectural complex in the Soviet Union illustrates the euphoria and the hope of people in this time, among so many other aspects. […] The transparency and openness of architecture and the generous scale of the facility are in a sense metaphoric of a sigh of relief following the Stalinist terror. […] Artek was supposed to be a beacon showing the world the new age in the Soviet Union.”[13]

Small addendum

Certainly not everything that today strikes us as acceptable or even worth commemorating in the legacy of state socialism was wrested from those in power or was created in niches at a remove from the party. Even the „leading cadres“ of the party state were not the homogenous caste they are usually portrayed as today. These were people with rather different characters, with their own experiences and ideas, among which one was able, when necessary, to find allies.

In the publications on Artek I discovered a sheet with a sketch by Polyansky that I found touching and made me think of my own early years at the drawing board. There they were again, the dream-like, blissful hours of the unhindered explorer who, full of exuberance, illuminates the ground plan and the section of his waterside pavilion with one sun. To overcome gravity in such a way, to leave behind Euclidean space – this is not something that an accomplice of power is capable of pulling off, and I’ve also rarely seen a dissident who was so laid-back. I simply believe that we – to paraphrase Camus – have to imagine the architect of the New Artek as a happy individual. That his sketches would then actually bring forth buildings, this is something others have decided.

[01] Bohdan Tscherkes, „Zauber meiner Seele. Anatoli Poljanski und die Pionierrepublik Artek auf der Krim“, Glück Stadt Raum in Europa 1945–2000. Romana Schneider and Rudolf Stegers (eds). Basel: Birkhäuser, 2002, p. 76 ff.

[02] Ibid.

[03] Ibid.

[04] Arne Winkelmamnn, Das Pionierlager Artek. Realität und Utopie in der sowjetischen Architektur der sechziger Jahre. Dissertation at the Bauhaus University Weimar, 2003. PDF-Download: http://knigi.suuk.su/architektur_de-1.pdf

[05] Liv Falkenberg, „Neubauten in Artek“, Deutsche Architektur, Vol. 1 (1962), p. 46. In the German Democratic Republic Polyansky’s buildings were immediately presented by a number of illustrations in the professional journal Deutsche Architektur. This was immediately followed by a discussion of Pier Luigi Nervi’s „Palace of Labor“ that had just been completed in Turin.

[06] Bohdan Tscherkes, op. cit.

[07] Stefanie Flamm, „Im Paradies der Pioniere“, Mare, No. 34, October 2002.

[08] Martin Fröhlich, „Der Rundgang“, Bauwelt, vol. 16 (2000), p. 23.

[09] Bohdan Tscherkes, op. cit.

[10] Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper, „Das KdF-Bad Prora auf Rügen. Ein Versuch über Architektur und Moral“, Das Kunstwerk als Geschichtsdokument. Annette Tietenberg (ed.). Munich: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1999, p. 153.

[11] Ibid, p. 154.

[12] Benedikt Hotze, „Der verlassene Faschismus“, Baunetzwoche, No. 291, Oct. 12, 2012. Download: www.baunetz.de/cid/2981133

[13] Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper, op. cit., p. 157.

Für den Beitrag verantwortlich: Hintergrund

Ansprechpartner:in für diese Seite: Martina Frühwirth